Herein lies another sax-player's bain!

Saxophone reeds are usually made from natural cane, thick at the bottom, thinning gradually to the slightly curved top. It fits against the instrument's mouthpiece and is secured by a fixing called a ligature. Saxophone reeds (or the reed of any woodwind instrument) compress the air column from the player's mouth and force it through the mouthpiece and into the instrument in a regulated flow.

The reed also makes the air column vibrate, which helps produce the instrument's sound. Reeds vary from manufacturer to manufacturer and even within box batches.... As with the system of numbering mouthpiece openings, the world of reed numbering is equally non-standard! Generally though they are numbered one to five, with number one being the softest. A crucial aspect of learning to play sax is working up your lip muscles to properly control a reed. Softer reeds require less lip muscle, a worthwhile consideration when starting out. Beginners should start on a strength 1½ reed while they get used to the blowing and forming of their embouchure. As their muscles develop, then move on to a strength 2 or 2½.

The strength numbers merely indicate how 'thick' or rigid a reed is and as you've probably guessed the lower numbers denote thinner, more flexible reeds which vibrate more freely and are therefore easier to play. It's important to keep in mind that the ultimate hardness of the reeds you choose is not indicative of your level of playing ability. Once you get your instrument to behave, you'll be able to select a hardness level of reeds based on the sound you want to create. If you select a reed that's too soft for your horn, it will sound raspy and generally unpleasant. Harder reeds require more lung power to play. Metal mouthpieces tend to require slightly softer reeds than their ebonite equivalent, but as with anything, much of this is ultimately down to the type of sound you're happy with and the comfort of blowing.

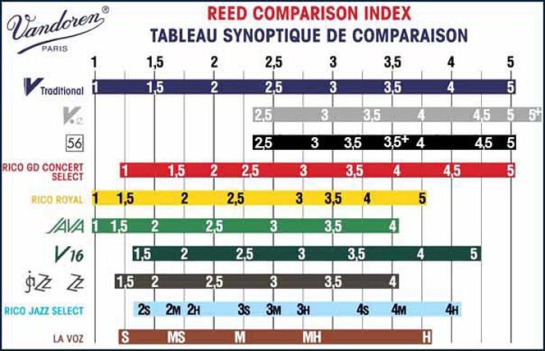

I use the Rico Jazz Select range, but that's just my preference. I've shown comparison charts for reed strengths by Rico (California) and Vandoren (France) when compared by manufacturer.

How a reed is made

Would you believe it takes four years to make a reed!

Cane is grown from rhizomes (rootlike subterranean stems, commonly horizontal in position, that produce roots below and send up shoots) and reaches its final size and diameter in the first year. It is carefully harvested at the end of the second year by hand using shears which avoid bursting the cane's fibres. The harvest is carried out while the moon is descending when the sap is utterly still. The cane is then stripped, cut into six-feet-long sticks and put out in the sun to gain its golden colour before being taken to a ventilated warehouse to dry for another two years.

The first stage in manufacture involves cutting the cane into smaller lengths and then into standard 'reed size' quarters. The bark of the tip is then removed and the table sanded completely flat. After cutting the reed into a conical shape the final reed tip is shaped & bevelled to within tolerances of 1/100 mm. Being an organic product, every reed has its own character as no two pieces of cane can be identical.

So next time you buy a reed, take a moment to consider the time involved in making it and getting it to you!

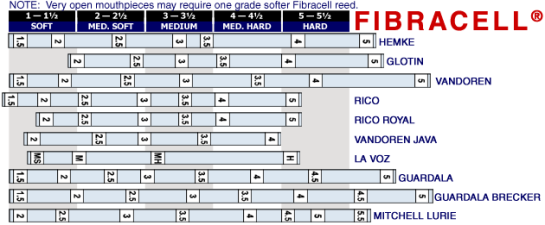

A relatively recent development in reed 'technology' has been the use of plastic in the reed manufacturing process. This is in the form of either plastic-coated cane reeds, or reeds made entirely from plastic. These are more expensive to buy in the first instance but are far more durable, consistent, more resistant to climatic changes and resist 'curling' when first moistened. These make them ideal for outside use such as marching bands or 'doublers' who need to change instruments quickly. The comparisons between the plastic 'Fibracell' reed and cane reed strengths are show here:

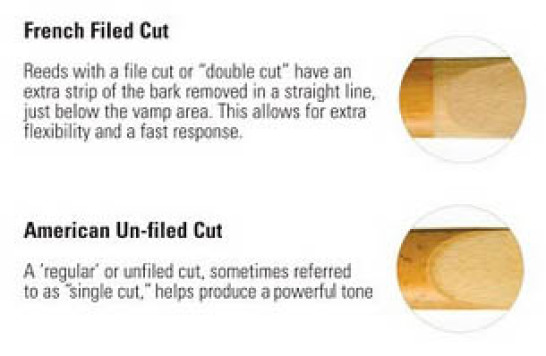

Filed vs Unfiled reeds

Many people ask about the difference between filed and unfiled reeds.

Here's a brief explanation:

An option to fine-tune the sound, the filed reed is often preferred by players who use traditional, moderately resistant, dark-sounding mouthpieces – the file helps such mouthpieces blow more freely.

For those who play relatively easy-blowing, moderate-to-bright mouthpieces (especially jazz or pop sax mouthpieces with a high baffle),an unfiled reed is usually preferred.

The French File (or “file”) is the area behind the vamp (or cut portion) where the bark is sanded off in a straight line.

A filed reed:

• Provides ease of response, especially in the low register...making soft attacks easier.

• Makes the tone slightly brighter...for use with resistant mouthpieces.

• Provides a brighter tone and is more free-blowing.

An unfiled reed provides a darker tone and more resistance.

Recommended use of filed or unfiled reeds for common sax mouthpieces:

Filed: • Meyer • Otto Link • Selmer rubber

Unfiled: • Dukoff • Beechler • Selmer metal • Guardala • Berg Larsen